Politics seems to have been of interest to Swift early in his career chiefly to the extent that it affected the strength and stability of the Anglican Church (in both England and Ireland) of which he was a member. The restoration of the Catholic monarchy, which was a real threat during his lifetime, would, he feared, result in "Papist" absolutism; in the loss of the liberties, privileges, and freedoms which the English Constitution granted to Protestants, if not to Catholics or Dissenters. Between the Restoration and James II's final flight to France, it had appeared not at all unlikely, to members of Swift's social class in England as in Ireland, that the English monarchy might relapse into a religious and political despotism. When James II succeeded his brother Charles II in 1685, and began gradually to reintroduce Catholics into key positions in the government and the army — and when, in 1688, he produced a male heir, thereby raising the possibility of an English Catholic Dynasty, the result was the bloodless Glorious Revolution, which Swift supported: William of Orange, proclaiming himself the defender of English freedoms, landed in England with 15,000 troops, while James, his popular support evaporating, fled to France.

The Revolution made English constitutionalism much more secure: the powers of the monarchy were severely limited, while those of parliament were strengthened. Supreme legislative power derived from a complex alliance between the King, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons: executive power resided with the king, but had to be lawfully exercised, while governmental ministers were liable to prosecution and impeachment if they behaved improperly. Respect for the civil and religious liberties of the subject (the loyal subject) was strongly emphasized.

Early in his life Swift was a member of the Whig party. The Whig government's flirtation with the Dissenters, however, helped to drive him, at at time when it seemed, in any case, to be a change which might advance his career, into the Tory camp. When Queen Anne died, however, and the Tory Government fell, he lost forever the chance of religious preferment in England which he had coveted for so long. The political pamphlets, however, which he would ultimately produce while he lived in what was for him a strange kind of exile in his native Ireland — the tracts and satires like "A Modest Proposal" (text) in which he defended the interests of his church and his class (and, by implication, his country) against what he had come increasingly to recognize as English colonialism — made him enormously popular, late in his life, in a country which he despised. He was idolized by a people the vast majority of whom, since they were Roman Catholics, he would have denied religious and political freedom. After his death he became a national hero and, more importantly, was perceived as having been a nationalist leader — which, in a real though limited sense, he certainly was.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

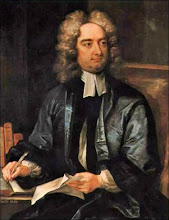

Jonathan Swift's Religious Beliefs

Swift was a clergyman, a member of the Church of Ireland, the Irish branch of the Anglican Church; and as such he was a militant defender of his church (and his own career prospects) in the face of the threats to its continued existence posed by Roman Catholicism at home in Ireland (which was overwhelmingly Catholic) and in England, where Swift and his peers saw the Catholics (and, at the other religious and political extreme, the Dissenters) as threatening not only the Anglican Church but the English Constitution.

Swift was ostensibly a conservative by nature: he instinctively sought stability in religion as in politics, but stability which insured personal freedoms. Indeed, so far as he was concerned, religion, morality, and politics were inseparable: he consistently attacked theological attempts (even within Anglicanism itself) to define and limit orthodoxy — attempts which, he felt, led ultimately to anarchic dissent. The divisive tendencies of Mankind had, he believed, over the centuries, promoted the general decay of Christianity itself, which had lost its original clarity, simplicity, and coherence. The Truth had been mishandled, corrupted, by men who had behaved like Yahoos. He adhered to the tenets of the Anglican Church because he had been brought up to respect them, because the Church of Ireland was the church of his social class, and because his own ambitions were involved in its success, but also because he saw the Church as a force for rationality and moderation; as occupying a perilous middle ground between the opposing adherents of Rome and Geneva.

Underlying all of Swift's religious concerns, underlying his apparent conservatism, which was really a form of radicalism, was his belief that in Man God had created an animal which was not inherently rational but only capable, on occasion, of behaving reasonably: only, as he put it, rationis capax. It is our tendency to disappoint, in this respect, that he rages against: his works embody his attempts to maintain order and reason in a world which tended toward chaos and disorder, and he concerned himself more with the concrete social, political, and moral aspects of human nature than with the abstractions of philosophy, theology, and metaphysics.

Swift was ostensibly a conservative by nature: he instinctively sought stability in religion as in politics, but stability which insured personal freedoms. Indeed, so far as he was concerned, religion, morality, and politics were inseparable: he consistently attacked theological attempts (even within Anglicanism itself) to define and limit orthodoxy — attempts which, he felt, led ultimately to anarchic dissent. The divisive tendencies of Mankind had, he believed, over the centuries, promoted the general decay of Christianity itself, which had lost its original clarity, simplicity, and coherence. The Truth had been mishandled, corrupted, by men who had behaved like Yahoos. He adhered to the tenets of the Anglican Church because he had been brought up to respect them, because the Church of Ireland was the church of his social class, and because his own ambitions were involved in its success, but also because he saw the Church as a force for rationality and moderation; as occupying a perilous middle ground between the opposing adherents of Rome and Geneva.

Underlying all of Swift's religious concerns, underlying his apparent conservatism, which was really a form of radicalism, was his belief that in Man God had created an animal which was not inherently rational but only capable, on occasion, of behaving reasonably: only, as he put it, rationis capax. It is our tendency to disappoint, in this respect, that he rages against: his works embody his attempts to maintain order and reason in a world which tended toward chaos and disorder, and he concerned himself more with the concrete social, political, and moral aspects of human nature than with the abstractions of philosophy, theology, and metaphysics.

A Chronology of Jonathan Swift's Life

1667 Jonathan Swift born on November 30 in Dublin, Ireland; the son of Anglo-Irish parents. His father dies a few months before Swift is born.

1673 At the age of six, Swift begins his education at Kilkenny Grammar School, which was, at the time, the best in Ireland.

1682-1686 Swift attends, and graduates from, Trinity College, Dublin

1688 William of Orange invades England, initiating the Glorious Revolution in England. With Dublin in political turmoil, Trinity College is closed, and Swift goes to England.

1689 Swift becomes secretary in the household of Sir William Temple at Moor Park in Surrey. Swift reads extensively in Temple's library, and meets Esther Johnson, who will become his "Stella." He first begins to suffer from Meniere's Disease, a disturbance of the inner ear.

1690 At the advice of his doctors, Swift returns to Ireland.

1691 Swift, back with Temple in England, visits Oxford.

1692 Temple enables Swift to receive an M. A. degree from Oxford, and Swift publishes first poem.

1694 Swift leaves Temple's household and returns to Ireland to take holy orders.

1695 Swift ordained as a priest in the Church of Ireland, the Irish branch of the Anglican Church.

1696-1699 Swift returns to Moor Park, and composes most of A Tale of a Tub, his first great work. In 1699 Temple dies, and Swift travels to Ireland as chaplain and secretary to the Earl of Berkeley.

1700 Swift instituted Vicar of Laracor, and presented to the Prebend of Dunlavin in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

1701 Swift awarded D. D. from Dublin University, and publishes his first political pamphlet, supporting the Whigs against the Tories.

1704 Anonymous publication of Swift's A Tale of a Tub, The Battle of the Books, and The Mechanical Operation of the Spirit.

1707 Swift in London as emissary of Irish clergy seeking remission of tax on Irish clerical incomes. His requests are rejected by the Whig government. He meets Esther Vanhomrigh, who will become his "Vanessa." During the next few years he is back and forth between Ireland and England, where he is involved in the highest political circles.

1708 Swift meets Addison and Steele, and publishes the Bickerstaff Papers and An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity.

1710 Swift returns to England. Publication of "A Description of a City Shower." Swift falls out with Whigs, allies himself with the Tories, and becomes editor of the Tory newspaper The Examiner.

1710 Swift writes the series of letters which will be published as The Journal to Stella.

1713 Swift installed as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin.

1714 Foundation of Scriblerus Club. Queen Anne dies, George I takes the throne, the Tories fall from power, and Swift's hopes for preferment in England come to an end: he returns to Ireland "to die," as he says, "like a poisoned rat in a hole."

1716 Swift marries? Stella (Esther Johnson).

1718 Swift begins to publish tracts on Irish problems.

1720 Swift begins work upon Gulliver's Travels, intended, as he says in a letter to Pope, "to vex the world, not to divert it."

1724 Publication of The Drapier Letters, which gain him enormous 1725 popularity in Ireland. Gullivers Travels completed.

1726 Visit to England, where he visits with Pope at Twickenham; publication of Gulliver's Travels.

1727 Swift's Last trip to England.

1727-1736 Publication of five volumes of Swift-Pope Miscellanies.

1728 Death of Stella.

1729 Publication of Swift's A Modest Proposal.

1731 Publication of Swift's "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed."

1735 Collected edition of Swift's Works published in Dublin; Swift is suffering from Meniere's Disease, resulting in periods of dizziness and nausea, and his memory is deteriorating.

1738 Swift slips gradually into senility, and suffers a paralytic stroke.

1742 Guardians appointed to care for Swift's affairs.

1745 Swift dies on October 19. The following is Yeats's poetic version (a very free translation) of the Latin epitaph which Swift composed for himself:

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

1673 At the age of six, Swift begins his education at Kilkenny Grammar School, which was, at the time, the best in Ireland.

1682-1686 Swift attends, and graduates from, Trinity College, Dublin

1688 William of Orange invades England, initiating the Glorious Revolution in England. With Dublin in political turmoil, Trinity College is closed, and Swift goes to England.

1689 Swift becomes secretary in the household of Sir William Temple at Moor Park in Surrey. Swift reads extensively in Temple's library, and meets Esther Johnson, who will become his "Stella." He first begins to suffer from Meniere's Disease, a disturbance of the inner ear.

1690 At the advice of his doctors, Swift returns to Ireland.

1691 Swift, back with Temple in England, visits Oxford.

1692 Temple enables Swift to receive an M. A. degree from Oxford, and Swift publishes first poem.

1694 Swift leaves Temple's household and returns to Ireland to take holy orders.

1695 Swift ordained as a priest in the Church of Ireland, the Irish branch of the Anglican Church.

1696-1699 Swift returns to Moor Park, and composes most of A Tale of a Tub, his first great work. In 1699 Temple dies, and Swift travels to Ireland as chaplain and secretary to the Earl of Berkeley.

1700 Swift instituted Vicar of Laracor, and presented to the Prebend of Dunlavin in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

1701 Swift awarded D. D. from Dublin University, and publishes his first political pamphlet, supporting the Whigs against the Tories.

1704 Anonymous publication of Swift's A Tale of a Tub, The Battle of the Books, and The Mechanical Operation of the Spirit.

1707 Swift in London as emissary of Irish clergy seeking remission of tax on Irish clerical incomes. His requests are rejected by the Whig government. He meets Esther Vanhomrigh, who will become his "Vanessa." During the next few years he is back and forth between Ireland and England, where he is involved in the highest political circles.

1708 Swift meets Addison and Steele, and publishes the Bickerstaff Papers and An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity.

1710 Swift returns to England. Publication of "A Description of a City Shower." Swift falls out with Whigs, allies himself with the Tories, and becomes editor of the Tory newspaper The Examiner.

1710 Swift writes the series of letters which will be published as The Journal to Stella.

1713 Swift installed as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin.

1714 Foundation of Scriblerus Club. Queen Anne dies, George I takes the throne, the Tories fall from power, and Swift's hopes for preferment in England come to an end: he returns to Ireland "to die," as he says, "like a poisoned rat in a hole."

1716 Swift marries? Stella (Esther Johnson).

1718 Swift begins to publish tracts on Irish problems.

1720 Swift begins work upon Gulliver's Travels, intended, as he says in a letter to Pope, "to vex the world, not to divert it."

1724 Publication of The Drapier Letters, which gain him enormous 1725 popularity in Ireland. Gullivers Travels completed.

1726 Visit to England, where he visits with Pope at Twickenham; publication of Gulliver's Travels.

1727 Swift's Last trip to England.

1727-1736 Publication of five volumes of Swift-Pope Miscellanies.

1728 Death of Stella.

1729 Publication of Swift's A Modest Proposal.

1731 Publication of Swift's "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed."

1735 Collected edition of Swift's Works published in Dublin; Swift is suffering from Meniere's Disease, resulting in periods of dizziness and nausea, and his memory is deteriorating.

1738 Swift slips gradually into senility, and suffers a paralytic stroke.

1742 Guardians appointed to care for Swift's affairs.

1745 Swift dies on October 19. The following is Yeats's poetic version (a very free translation) of the Latin epitaph which Swift composed for himself:

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

Jonathan Swift Biography

Jonathan Swift was born on November 30, 1667 in Dublin, Ireland, the son of Protestant Anglo-Irish parents: his ancestors had been Royalists, and all his life he would be a High-Churchman. His father, also Jonathan, died a few months before he was born, upon which his mother, Abigail, returned to England, leaving her son behind, in the care of relatives. In 1673, at the age of six, Swift began his education at Kilkenny Grammar School, which was, at the time, the best in Ireland. Between 1682 and 1686 he attended, and graduated from, Trinity College in Dublin, though he was not, apparently, an exemplary student.

In 1688 William of Orange invaded England, initiating the Glorious Revolution: with Dublin in political turmoil, Trinity College was closed, and an ambitious Swift took the opportunity to go to England, where he hoped to gain preferment in the Anglican Church. In England, in 1689, he became secretary to Sir William Temple, a diplomat and man of letters, at Moor Park in Surrey. There Swift read extensively in his patron's library, and met Esther Johnson, who would become his "Stella," and it was there, too, that he began to suffer from Meniere's Disease, a disturbance of the inner ear which produces nausea and vertigo, and which was little understood in Swift's day. In 1690, at the advice of his doctors, Swift returned to Ireland, but the following year he was back with Temple in England. He visited Oxford in 1691: in 1692, with Temple's assistance, he received an M. A. degree from that University, and published his first poem: on reading it, John Dryden, a distant relation, is said to have remarked "Cousin Swift, you will never be a poet."

In 1694, still anxious to advance himself within the Church of England, he left Temple's household and returned to Ireland to take holy orders. In 1695 he was ordained as a priest in the Church of Ireland, the Irish branch of the Anglican Church, and the following year he returned to Temple and Moor Park.

Between 1696 and 1699 Swift composed most of his first great work, A Tale of a Tub, a prose satire on the religious extremes represented by Roman Catholicism and Calvinism, and in 1697 he wrote The Battle of the Books, a satire defending Temple's conservative but beseiged position in the contemporary literary controversy as to whether the works of the "Ancients" — the great authors of classical antiquity — were to be preferred to those of the "Moderns." In 1699 Temple died, and Swift traveled to Ireland as chaplain and secretary to the Earl of Berkeley.

In 1700 he was instituted Vicar of Laracor — provided, that is, with what was known as a "Living" — and given a prebend in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. These appointments were a bitter disappointment for a man who had longed to remain in England. In 1701 Swift was awarded a D. D. from Dublin University, and published his first political pamphlet, supporting the Whigs against the Tories. 1704 saw the anonymous publication of A Tale of a Tub, The Battle of the Books, and The Mechanical Operation of the Spirit.

In 1707 Swift was sent to London as emissary of Irish clergy seeking remission of tax on Irish clerical incomes. His requests were rejected, however, by the Whig government and by Queen Anne, who suspected him of being irreligious. While in London he he met Esther Vanhomrigh, who would become his "Vanessa." During the next few years he went back and forth between Ireland and England, where he was involved — largely as an observer rather than a participant — in the highest English political circles.

In 1708 Swift met Addison and Steele, and published his Bickerstaff Papers, satirical attacks upon an astrologer, John Partridge, and a series of ironical pamphlets on church questions, including An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity.

In 1710, which saw the publication of "A Description of a City Shower," Swift, disgusted with their alliance with the Dissenters, fell out with Whigs, allied himself with the Tories, and became the editor of the Tory newspaper The Examiner. Between 1710 and 1713 he also wrote the famous series of letters to Esther Johnson which would eventually be published as The Journal to Stella. In 1713 Swift was installed as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin — a promotion which was, again, a disappointment.

The Scriblerus Club, whose members included Swift, Pope, Congreve, Gay, and Arbuthnot, was founded in 1714. In the same year, much more unhappily for Swift, Queen Anne died, and George I took the throne. With his accession the Tories fell from power, and Swift's hopes for preferment in England came to an end: he returned to Ireland "to die," as he says, "like a poisoned rat in a hole." In 1716 Swift may or may not have married Esther Johnson. A period of literary silence and personal depression ensued, but beginning in 1718, he broke the silence, and began to publish a series of powerful tracts on Irish problems.

In 1720 he began work upon Gulliver's Travels, intended, as he says in a letter to Pope, "to vex the world, not to divert it." 1724-25 saw the publication of The Drapier Letters, which gained Swift enormous popularity in Ireland, and the completion of Gulliver's Travels. The progressive darkness of the latter work is an indication of the extent to which his misanthropic tendencies became more and more markedly manifest, had taken greater and greater hold upon his mind. In 1726 he visited England once again, and stayed with Pope at Twickenham: in the same year Gulliver's Travels was published.

Swift's final trip to England took place in 1727. Between 1727 and 1736 publication of five volumes of Swift-Pope Miscellanies. "Stella" died in 1728. In the following year A Modest Proposal was published. 1731 saw the publication of Swift's ghastly "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed."

By 1735, when a collected edition of his Works was published in Dublin, his Meniere's Disease became more acute, resulting in periods of dizziness and nausea: at the same time, prematurely, his memory was beginning to deteriorate. During 1738 he slipped gradually into senility, and finally suffered a paralytic stroke: in 1742 guardians were officially appointed to care for his affairs.

Swift died on October 19, 1745. The following is Yeats's poetic version (a very free translation) of the Latin epitaph which Swift composed for himself:

Swift sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

In 1688 William of Orange invaded England, initiating the Glorious Revolution: with Dublin in political turmoil, Trinity College was closed, and an ambitious Swift took the opportunity to go to England, where he hoped to gain preferment in the Anglican Church. In England, in 1689, he became secretary to Sir William Temple, a diplomat and man of letters, at Moor Park in Surrey. There Swift read extensively in his patron's library, and met Esther Johnson, who would become his "Stella," and it was there, too, that he began to suffer from Meniere's Disease, a disturbance of the inner ear which produces nausea and vertigo, and which was little understood in Swift's day. In 1690, at the advice of his doctors, Swift returned to Ireland, but the following year he was back with Temple in England. He visited Oxford in 1691: in 1692, with Temple's assistance, he received an M. A. degree from that University, and published his first poem: on reading it, John Dryden, a distant relation, is said to have remarked "Cousin Swift, you will never be a poet."

In 1694, still anxious to advance himself within the Church of England, he left Temple's household and returned to Ireland to take holy orders. In 1695 he was ordained as a priest in the Church of Ireland, the Irish branch of the Anglican Church, and the following year he returned to Temple and Moor Park.

Between 1696 and 1699 Swift composed most of his first great work, A Tale of a Tub, a prose satire on the religious extremes represented by Roman Catholicism and Calvinism, and in 1697 he wrote The Battle of the Books, a satire defending Temple's conservative but beseiged position in the contemporary literary controversy as to whether the works of the "Ancients" — the great authors of classical antiquity — were to be preferred to those of the "Moderns." In 1699 Temple died, and Swift traveled to Ireland as chaplain and secretary to the Earl of Berkeley.

In 1700 he was instituted Vicar of Laracor — provided, that is, with what was known as a "Living" — and given a prebend in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. These appointments were a bitter disappointment for a man who had longed to remain in England. In 1701 Swift was awarded a D. D. from Dublin University, and published his first political pamphlet, supporting the Whigs against the Tories. 1704 saw the anonymous publication of A Tale of a Tub, The Battle of the Books, and The Mechanical Operation of the Spirit.

In 1707 Swift was sent to London as emissary of Irish clergy seeking remission of tax on Irish clerical incomes. His requests were rejected, however, by the Whig government and by Queen Anne, who suspected him of being irreligious. While in London he he met Esther Vanhomrigh, who would become his "Vanessa." During the next few years he went back and forth between Ireland and England, where he was involved — largely as an observer rather than a participant — in the highest English political circles.

In 1708 Swift met Addison and Steele, and published his Bickerstaff Papers, satirical attacks upon an astrologer, John Partridge, and a series of ironical pamphlets on church questions, including An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity.

In 1710, which saw the publication of "A Description of a City Shower," Swift, disgusted with their alliance with the Dissenters, fell out with Whigs, allied himself with the Tories, and became the editor of the Tory newspaper The Examiner. Between 1710 and 1713 he also wrote the famous series of letters to Esther Johnson which would eventually be published as The Journal to Stella. In 1713 Swift was installed as Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin — a promotion which was, again, a disappointment.

The Scriblerus Club, whose members included Swift, Pope, Congreve, Gay, and Arbuthnot, was founded in 1714. In the same year, much more unhappily for Swift, Queen Anne died, and George I took the throne. With his accession the Tories fell from power, and Swift's hopes for preferment in England came to an end: he returned to Ireland "to die," as he says, "like a poisoned rat in a hole." In 1716 Swift may or may not have married Esther Johnson. A period of literary silence and personal depression ensued, but beginning in 1718, he broke the silence, and began to publish a series of powerful tracts on Irish problems.

In 1720 he began work upon Gulliver's Travels, intended, as he says in a letter to Pope, "to vex the world, not to divert it." 1724-25 saw the publication of The Drapier Letters, which gained Swift enormous popularity in Ireland, and the completion of Gulliver's Travels. The progressive darkness of the latter work is an indication of the extent to which his misanthropic tendencies became more and more markedly manifest, had taken greater and greater hold upon his mind. In 1726 he visited England once again, and stayed with Pope at Twickenham: in the same year Gulliver's Travels was published.

Swift's final trip to England took place in 1727. Between 1727 and 1736 publication of five volumes of Swift-Pope Miscellanies. "Stella" died in 1728. In the following year A Modest Proposal was published. 1731 saw the publication of Swift's ghastly "A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed."

By 1735, when a collected edition of his Works was published in Dublin, his Meniere's Disease became more acute, resulting in periods of dizziness and nausea: at the same time, prematurely, his memory was beginning to deteriorate. During 1738 he slipped gradually into senility, and finally suffered a paralytic stroke: in 1742 guardians were officially appointed to care for his affairs.

Swift died on October 19, 1745. The following is Yeats's poetic version (a very free translation) of the Latin epitaph which Swift composed for himself:

Swift sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)